Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that this webpage contains images of deceased persons.

Australian aboriginal people have been, it is estimated, in the coastal Wangetti region for at least 40,000 years, although their habitation of the rainforest may only have been during the last 5,100 years.

Originally, there were four main tribes that frequented the area. The Kuku Yalanji lived predominantly in the rainforest to the north, beyond the Mowbray River. To the south and south west of Cairns were the Yidinji, and to the west the Djabugay. The narrow coastal strip however, from what is now Cairns to Port Douglas, belonged to the Yirrganydji, and it is to this day that the scions of that tribe still lay claim to the Wangetti region as their traditional tribal lands.

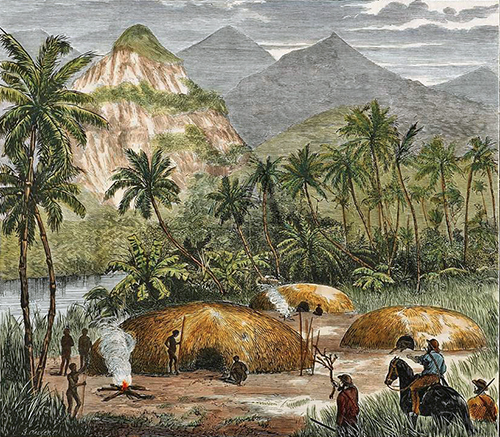

The area now known as Wangetti was originally a meeting place for the three tribes who inhabited this area. The Yirrganydji, being the traditional group in this area. The Djabugay, who came down from the westerly walking tracks, and the Kuku Yalanji, who came from the north. The groups would meet there, and at a place close to what is now Palm Cove, at various times of the year to trade.

The Yirrganydji travelled the area between what is now Trinity Inlet to Port Douglas. They were the coastal speakers of the Djabugay language. These people moved up and down this coastal strip as a hunter/gatherer society. The Yirrganydji had an intimate knowledge of their land, its flora and fauna, and its weather patterns. They were a rainforest dwelling and seafaring people, using the resources of both environments for their food and clothing.

In the dreaming, the Yirrganydji tell the story of the Rainbow Serpent, who made all the rivers and creeks within their area. After the work was over, the Rainbow Serpent turned itself into a large Carpet Snake and lies curled up near a large rock, sunning itself on what we call Double Island or Wangal Djungay, meaning place where the fast moving Storytime Boomerang landed.

The Yirrganydji traded: square-cut Nautilus shell necklaces; dilly baskets; bent moon-shaped woomeras; large fighting shields; and long, single-handle rainforest swords, with other tribal groups. Because of the abundance of food resources in this small area, the Yirrganydji had permanent camps back from the beach area. These permanent structures were nearly eight meters in diameter. They housed up to three families at a time. At night, fires would be lit near the entrance of these houses to ward off the mosquitoes and sandflies.

Because the freshwater met the saltwater here, the spawning of various varieties of fish took place in the upper reaches of what's now called Hartleys Creek. With their Red Cedar outrigger canoes, the Yirrganydji fished the reefs nearby too. Some of the types of fish caught were Barramundi, Red Bream, Black Bream, Shovelnose Ray, Catfish and various types of shellfish. Dugong and Turtle were also caught. The people also used many types of bush tucker.

During the dry winter months, fruit bearing trees such as the Burdekin Plum were plentiful. Other nut-bearing trees were available at this time too. The women had a vast knowledge of the different food resources. Their time was taken up with foraging for food. The gathering of shellfish was one of the many tasks done by women, while the men mainly fished and hunted.

Some of the nuts gathered by the women were poisonous and were placed in a dilly basket in a slow moving stream, where the water flushed out the toxins. After about two days, the harmful substances would have been leached and the women would gather the food from the dilly basket and prepare a type of what we call today, damper. Other times were taken up with preparing vegetable foods and taking care of young.

A stone tool manufacturing site and a spear-sharpening site still exist in the area to this day.

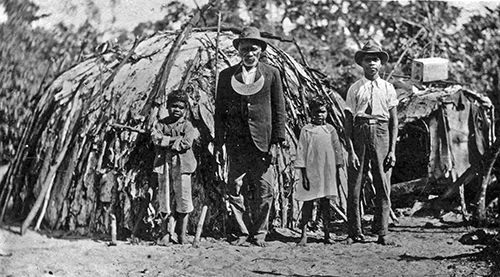

Today, the descendants of Yirrganydji leader Billy Jagar's (1870-1930) Lower Barron River and Hospital Camp group live at Yarrabah and Cairns. The Yirrganydji have maintained their spiritual and cultural connections to the land of their forebears, and are continuing to teach the younger generations about their ancient culture.

According to Norman Tindale, one of Australia's most well respected aboriginal anthropologists and ethnologists, the Yirrganydji territory extended over some 520 km2, the inland extension going about 11 kms northwest of Cairns, around the tidal waters of the Barron River near Redlynch. They spoke Yirrgay, one of five dialects of the language group generally known as Djabugay, which in turn was genetically related to Yidiny (the language of the Yidinji).

In 1873, following the discovery of gold on the Palmer River, the entire area became subject to a government settlement campaign, during which European settlers were encouraged to take up lands that traditionally belonged to aboriginal peoples. The narrow, but fertile land strip belonging to the Yirrganydji was one of the first to be seized. Over the following years, with the official establishment of Cairns in 1876 and Port Douglas in 1877, the Yirrganydji found it increasingly more difficult to continue their traditional hunting, foraging and fishing practices. Many were forced to enter into work agreements in the local towns, just to secure a food supply. Quite a number, having lost their established campsite areas on the coast, either fled to the rainforest, where they had to outrun the loggers, or allowed themselves to be placed in aboriginal reserve areas in Mona Mona or Yarrabah.

In 1897, William Parry-Okeden, the Brisbane-based Police Commissioner and Protector Of Aborigines, believed that the Yirrganydji tribe was close to extinction, however Billy Jagar, the commonly accepted leader of the Yirrganydji, still lived with many of his kin in a small camp at the northern end of the Cairns Esplanade. The following year (1898), Billy Jagar was awarded a King Plate, aknowledging him as the King Of The Barron. The award was repeated in 1908 with a similar plate. Billy Jagar died in 1930, at the age of 60, while still residing in his small camp just north of the Cairns Hospital.

As of 2016, The Yirrganydji people of Cairns and surrounds currently have a Native Title Determination Application with the Federal Court of Australia, covering a large area of land from the Barron River in the south, to the Mowbray River in the north, and close to Mareeba in the west.

The Yirrganydji, along with the other rainforest dwelling traditional owners in the Wet Tropics QLD World Heritage Area, now have strong representation in management of this area. This is done through the Wet Tropics Management Authority, via the Rainforest Aboriginal Peoples' Alliance and the Traditional Owners Leadership Group.

Locally, this has been further enhanced by the establishment of the Yirrganydji Land And Sea Ranger program.

Identification of traditional Yirrganydji sites and restoration of artefacts is an ongoing project for all Yirrganydji people. Much work has been done already with the full cooperation of the WTMA.

The Djabugay people are the original inhabitants (from at least 10,000 years ago) of the predominantly rainforested lands between the Lamb Range - Harris Peak (Black Mountain) coastal escarpment to the east, and the Tolga to Mount Molloy area, to the west. The most important area for the Djabugay was the Barron Gorge - Kuranda region. The name for Kuranda was "Ngunbay", meaning place of the Platypus. Their language group includes the Djabuganydji, Bulwanydji, Nyagali, Yirrganydji and Gulunydji First Nations peoples.

Before white settlers first arrived in the area, the Djabugay population was around 4500, but their numbers quickly diminished as the "Gadja" (white men) infiltrated, seeking gold, tin, lumber and agricultural land. The Djabugay peoples fiercely resisted the infiltration and many lop-sided confrontations between the two groups occurred.

"Dispersals", the euphemism for shooting groups of blacks, were undertaken at Smithfield (1878), at Biboohra near the Clohesy River close to Kuranda in the early 1880s, and also near Mareeba in 1881. In 1886, construction began on a railway from Cairns to Herberton, with part of the rails going over a traditional walking track. The Djabugay were unhappy about this development and withstood the settlement by spearing bullocks and settlers. This led to the notorious Speewah massacre in 1890 where John Atherton took revenge on the Djubagay by sending in native troopers to avenge the killing of a bullock. As the settlers entered, traditional hunting and gathering grounds were taken over, and by the turn of the century, Djabugay numbers had fallen dramatically.

In 1913, many of the Djabugay became segregated and were forced to live at the Mona Mona Mission near Kuranda. Collectively, they were no longer able to hunt, fish or move around freely, as they had been doing for literally thousands of years.

The Mona Mona Mission, set up on the banks of Flaggy Creek north of Kuranda, was run by the Seventh Day Adventist church. Officially, the residents were Djabugay people, but in reality many were from other tribes in the region, and the vast majority were young people or children, forcibly removed from their families. The church (and of course the majority of white society) considered the venture an enormous success, citing the clean, well-dressed and well-nourished residents as proof that the "natives" could be trained to live as the whites did. Although the Mission operated self-sufficiently for many years, and the intentions of the Seventh Day Adventists running the Mission were no doubt noble, the forced separation of the young indigenous people from their families was a truly heart-wrenching time and became part of what was later referred to as the "stolen generations".

In 1962, the area around Flaggy Creek became ear-marked for a State Government dam project. This resulted in the closure of the Mona Mona Mission. The residents were dispersed into various other missions, such as Yarrabah, Palm Island and Woorabinda, or assimilated into many of the local established towns. Those who moved into the local towns gained employment in agriculture, the timber industry or in commerce. After several years, the State Government decided against the dam project and many of Mona Mona's former residents moved back onto the old mission lands, taking over what was left of the buildings and constructing other residences. In 2010, the Queensland Government granted the people of Mona Mona a 30 year lease on the area.

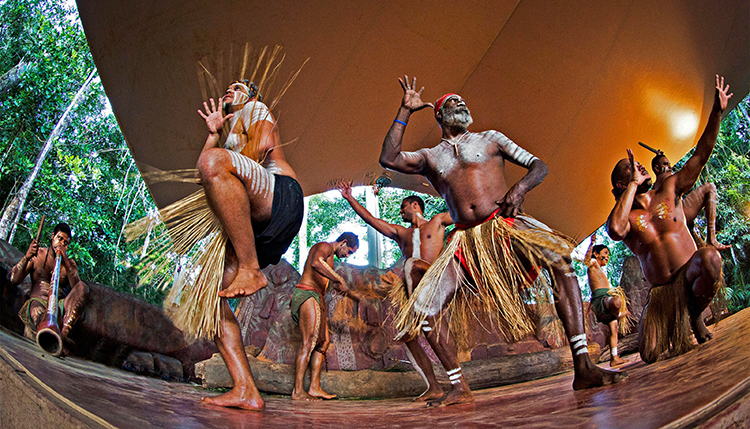

Today, the Djabugay people have continued their traditional customs by nurturing and passing on knowledge of dance, language and rainforest hunting/gathering. For many years the traditional dance and culture was celebrated and showcased at the Tjapukai Aboriginal Cultural Park in Smithfield.

The Djabugay peoples’ traditional lands include the Barron Gorge National Park in Queensland’s World Heritage listed Wet Tropics. The Barron Gorge National Park is an internationally renowned natural icon, and the Barron Falls (Din Din) an all powerful symbol of the significance of the area to the Traditional Owners. For the Djabugay people, a Native Title determination in 2004 recognised their connection to country as Traditional Owners, and gave an opportunity to have a say on the management of the park.

The Djabugay Aboriginal Corporations recently launched the Djabugay Bulmba Bama Plan which aims to guide the development of a joint management model towards social, cultural and economic benefits for the Djabugay people. The Corporations provide a range of programs, products and services which are geared to revitalising, maintaining and strengthening the Djabugay peoples’ culture, language and connection to their land, as well as equipping and providing them employment and sustainable economic opportunities. The Corporations currently run a range of programs including: (1) Djabugay Bulmba Rangers Program; (2) Horticulture & Asset Maintenance Program; (3) Language (Ngirrma) & Culture Program; (4) Djabugay Art Centre; (5) Didjirr Didjirr Family Network.