Cultural fire is fire deliberately put into the landscape, authorised and lead by the Traditional Owners of that Country, for a variety of purposes. Those purposes include, but are not limited to: ceremony; protection of cultural and natural assets; fuel reduction; regeneration and management of food, fibre and medicines; flora regeneration; fauna habitat protection and healing Country’s spirit.

Sick country needs fire to restore its health. One of the signs that country is sick is a heavy layer of leaf litter.

Fire is an important symbol in Aboriginal culture. Traditionally it was used as a practical tool in hunting, cooking, warmth and managing the landscape. It also holds great spiritual meaning, with many stories, memories and dance being passed down around the fire.

However, when out-of-control bush fires burn Aboriginal land, they are "also burning up our memories, our sacred places, all the things which make us who we are, because we lose forever what connects us to a place in the landscape".

Fire management is part of how Aboriginal people look after country. It is often called 'cultural burning'.

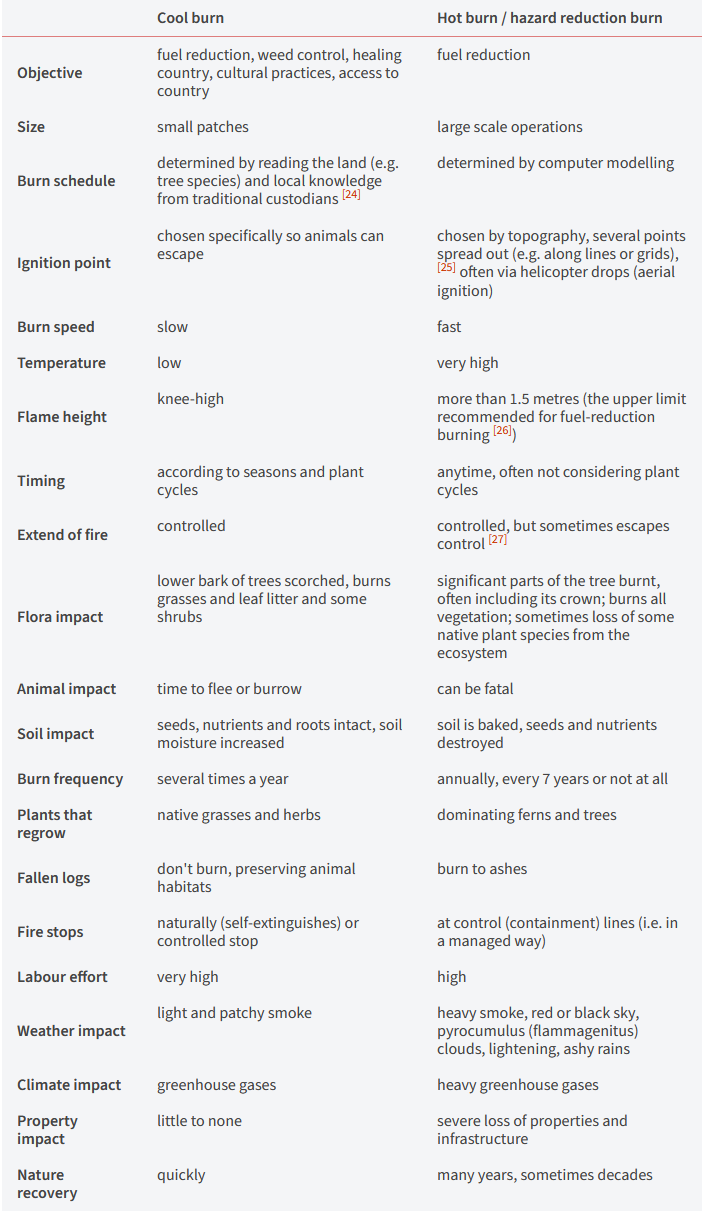

Traditional fire management applies cool and quick burns. These low-intensity fires are also known as cultural burning. They have several benefits:

- Save flora and fauna. Animals, including beetles and ant colonies, have enough time to escape. Young trees can survive and the fire keeps grass seeds intact for regrowth. The heat, which is much cooler than a hazard reduction burn, doesn't ignite the oil in a tree’s bark. It's a "tool for gardening the environment".

- Self-extinguishing. The fire extinguishes straight after it burns the grass (“self-extinguishing fire”).

- Avoids chemical weed killers. Introduced species, for example grasses, are not fire-resistant and can be removed with fire instead of chemicals.

You can tell if a fire was a cool burn when the burnt grass still has its previous shape.

Cultural burning is tightly connected to caring for country. It is applied more frequently than hazard reduction burning and is very labour intensive.

Cultural burns are used for cultural purposes and not simply for asset protection. They protect Aboriginal sites and clear access to country for cultural uses (e.g. hunting, access to fish traps, ceremony grounds).

Aboriginal control of preparation and implementation is essential.

After World War II, mission towns and cattle stations lured Aboriginal people away from their homelands with promises of work and education. Fire management stopped, with severe consequences for the land. Lightning strikes ignited large, hot fires late in the dry season, between August and December, when there was plenty of fuel.

This trend has not been reversed yet. "Since European settlement, fires in the north have increased in size and severity. This has threatened biodiversity as well as increased greenhouse gas emissions," says Dr Garry Cook from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

When Aboriginal people returned to country and properly managed it, the area that burned was cut in half. Fire is an inevitable force in the dry season and needs to be managed. Fire burning has created a variety of habitats including places that are very sensitive to fire like rainforest.

But cultural land management cannot just be added to existing non-Aboriginal practices. Aboriginal people must be involved as they know when to burn, where to burn and how to execute a burn.

The timing of fire management is critical and needs to happen at the right time of the year. To Aboriginal experts, the country reveals when it is appropriate to use fire: indicators such as when trees flower and native grasses cure. "The knowledge is held within the landscape. Once we learn how to read that landscape and interpret that knowledge, that’s when we can apply those fire practices," explains Aboriginal community member Noel Webster.

Ideal is the early dry season, from April to July, when vegetation that grew during the wet season begins to dry, fuel loads are low and wind patterns and dew support a burn. You don't want to burn when certain seeds or fruits are ripe for harvest.

The bushfire threat ends usually in November/December when monsoon rains arrive and the wet season returns.

If burning too early, big thick scrub develops after the fire which can become a big fuel load and is hard to manage.

If burning occurs too late, trees 'explode' during the fire and not much will be left after the fire goes through. Such fires emit higher levels of greenhouse gases than early season fires.

The right time depends on the ecosystem of the burn area because each system has its own identity and needs. An ecosystem is for example a forest of boxwood or tea trees, rainforest, or heath areas along rivers and springs.

A central idea in fire management is to have a cool fire. Night time or early mornings are ideal for cool fires as during the day plants sweat out flammable oils, and a nightly dew helps cool down the fire.

During a morning burn the wind is often gentle and supports Aboriginal people directing the burn. Without the help of the wind burning cannot happen at the right time. The sun, in contrast, encourages the fire to burn.

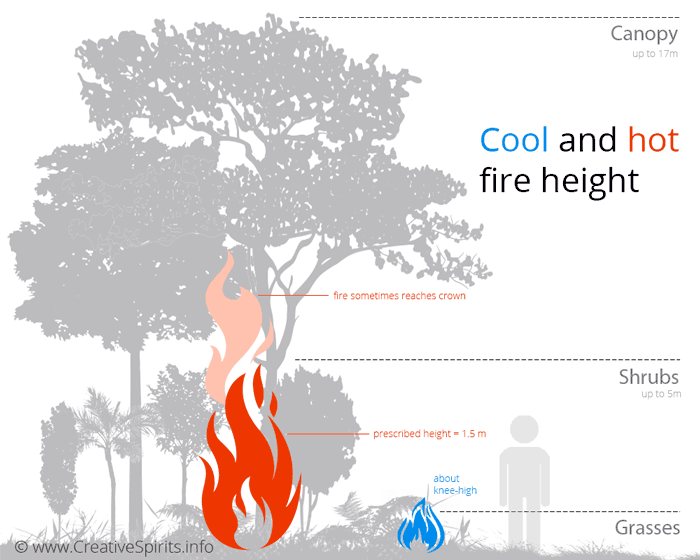

Cool fires don't bake the seeds and nutrients in the soil or destroy root systems. Flames are low so they cannot ignite the tree canopy and only char the bottom bark. They don't burn logs lying on the ground or habitat trees. Burning supports certain soils to improve and enables them to hold more moisture.

The speed of the fire is slow enough to allow insects to escape. If you cannot see an army of insects crawling and flying away from the fire, it is moving too fast and is too hot. The humans who manage the fire can also walk with the fire and correct if necessary.

Cool fires help change the vegetation structure by reducing the density of plants like Bracken Fern or Casuarina which lead to extreme fuel loads. But hot fires, such as hazard reduction burns, encourage their regrowth.

Aboriginal people who execute cool fires usually stay with the fire to manage it.

Like a non-Aboriginal person reads a book, Aboriginal people can read the land to determine which areas need fire management.

They prepare a burn by looking at the different ecosystems, patches, fuel loads, grasses, soil type, and the kinds of ashes a fire will leave behind. It is not “one big grass area to be burnt”.

Trees tell Aboriginal people about the soil type and this tells them what type of fire is needed. Aboriginal people know which areas will burn and where the fire is going to stop. Some areas "want to be burnt" while others need to rest and regrow.

Cultural burns burn "for country" and not to satisfy a certain number of hectares for bureaucrats or statistics.

"Indigenous [fire management] knowledge is really Indigenous science and must be recognised as this." - David Claudie, Kuuku I'yu Northern Kaanju traditional owner

Burning usually occurs at the edge of the next ecosystem, so to not affect it as it might require a different approach of fire management at a different time. Many small mammals and birds need ground to stay unburnt for at least three years.

Aboriginal fire management techniques cannot be applied universally or done at scale as they intricately depend on the landscape. What works in savannah in northern Queensland might not work in subtropical rainforests in New South Wales or eucalyptus forests in Victoria.

And not all fire knowledge has been preserved – in areas close to Australian cities, where invasion often wiped out entire Aboriginal nations, fire knowledge has died with them.

Aboriginal people read the systems of fire — the grass, soil type, what animals live there and how they benefit from it. Burning styles differ depending on how "sick" the land is.

To start a fire, Aboriginal people traditionally used a tea tree bark torch. Contemporary fire management uses either a kerosene bark torch (the oil in the bark keeps torch alive) or a drip torch (hot fires).

The first fire burns a circle around Aboriginal people’s living area so they are safe.

Early dry-season, cool fires trickle through the landscape and burn only some of the fuel, creating a network, or mosaic, of burnt firebreaks. These stop the late dry-season, hot fires.

A cool fire preserves the canopy of trees. This is very important for several reasons:

- Protection and provision. The canopy provides shade, fruit flowers and seeds. It allows animals to come back quickly.

- Carbon reduction. Unlike a cool burn, a canopy fire releases too much carbon. Local land managers employing cool burns can then sell carbon credits for the emissions avoided.

- Fire refugee. When there’s a fire insects and other small animals crawl up the tree to safety.

- Preserve tree cycle. With its canopy intact the tree does not miss its cyclic renewal.

- Trigger for germination. The smoke from a cool burn goes through the canopy and triggers off a reaction for seeds up there to germinate.

No wonder that Aboriginal people consider the trees' canopy "sacred".

This is in stark contrast to how non-Aboriginal people understand fire. “Non-Indigenous mob, their fires are based on their money,” complains David Claudie.

Non-Aboriginal people, like pastoralists or officers in land management departments and other government bodies, are trying to learn how to manage fire correctly on their own, but the knowledge is right there under their nose, with Aboriginal people. All they need to do is ask for help. Some do.

"The land has become sick and the land is pushing [pastoralists] to us [Aboriginal people]." - Victor Steffensen, Tagalaka man from North Queensland

"Fire cannot be managed from the air alone, you need to have people on the ground. The problem is not the fire, it’s people with no proper relationship with the land." - David Claudie

Hazard-reduction burns are deliberate, authorised fires to reduce fuel loads and threats to people and property from wildfires. They are also known as fuel reduction burns, prescribed, planned or controlled burns. These burns can often be much hotter than cool burns, with devastating consequences to the burnt areas.

Backburns are different – they are lit during an emergency to create a burnt buffer to stop an active bushfire and do not consider environmental impact.

Research shows that hazard reduction burning is not an effective method to prevent subsequent bush fires.

"Sick country needs fire to restore its health. One of the signs that country is sick is a heavy layer of leaf litter." - Sue Stevens, Reduce Your Footprint

The discussion around the sacred canopy of trees already indicated the intricate links between fire, animals and plants.

During a fire, bush turkeys hunt for bugs and insects at the fire line while hawks scour it for small animals.

Animals know how to protect themselves from fire: ants and snakes go deep down into their nests and burrows, kangaroos find safe spots on rocky outcrops.

Regular burning is also an effective weed control to introduced species like the African gamba grass which can increase fuel loads 10-fold.

After a fire, if it was cool, new grass is growing only weeks after a burn. It holds the soil together and provides a source of food for wombats, wallabies and native birds, and ample hunting opportunities prior to invasion. Brolgas (Australian cranes) eat insects that have been burnt.

Wallaby, birds and other animals bathe in the cool ash to cleanse themselves, for example to get rid of lice. The black coals can also be used as medicine.

Fire management is not without its critics. It divides tourism operators, bushwalkers, environmentalists, ecologists and archaeologists.

Some believe that that too much land is burnt too often, and that fighting fire with fire worsens what it should protect: the loss of habitat, decline of species, erosion, flooding and the destruction of Aboriginal rock art. Bushwalking businesses are concerned to lead their customers "through ash" while environmentalists stress that "good" fire regimes should maximise the extent of unburnt areas.

Another point of conflict arises when landowners are paid to burn early in the season, called savanna carbon farming. The fire stimulates grass regrowth, so carbon dioxide emissions from the fire are not included in emission calculations because it is assumed that vegetation regrowth removes an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

Farmers and landowners are reluctant to burn their land as kilometres of fences, often built using wooden posts, could catch fire. Their replacement can cost as much as a quarter million dollars, depending on the property size.

While Aboriginal custodians managed for thousands of years to preserve Aboriginal rock art within areas which were regularly burnt, current fire practices ("hazard reduction burns") might no longer guarantee the same result. Archaeologists claim that aerial burning is responsible for fading and scorching art and destroying as much as 30% of it in the Kimberley.

Aboriginal people understand that fire is part of the healing process of the land. Children as young as four learn how to lose their fear and manage fire.

Going back to their homelands, Aboriginal people want to heal the land from colonisation. Proper fire management is an essential part of this healing process. But it goes both ways – Aboriginal people who go out on country also reconnect with culture.

Elders share knowledge with younger generations of Aboriginal men who receive training from the Royal Fire Service. Cultural burning also complements the fire service’s hazard reduction burns in fire-prone areas.

As Aboriginal rangers increase their knowledge of how to manage fire, so rises their confidence and sense of identity. "Having the rangers here plays a big part in keeping identity alive and pride in what our people have," finds Aboriginal ranger Robin Dann.

Rangers burn vegetation to protect rainforest patches, rock art and traditional pathways. They track the progress of fires with online maps based on satellite images.

For thousands of years, Aboriginal people have used fire to hunt and to manage the landscape. Some scientists have argued that when people first arrived in Australia about 45,000 years ago they set a large number of these fires, which reshaped the country's ecosystems. This theory has become an accepted idea.

A study from the University of Tasmania examined this theory by analysing the genetic fingerprints of a particular fire-sensitive tree found across the continent.

It found that fluctuations in populations of these trees across the continent since the arrival of people were driven primarily by climate, not fire. Aboriginal use of fire seems not to have caused a major restructuring of vegetation across the continent.

"The effect of Aboriginal landscape burning is a lot more subtle. It's still important, but it's subtle and it's region-specific," the researchers concluded.